Leaves exhibit two primary forms: simple (a single blade) or compound (composed of multiple leaflets). The intricate and varied morphology of compound leaves has long fascinated plant biologists, driving research into how plants develop such complex structures and the genetic foundations of their remarkable diversity.

In a study published in Current Opinion in Plant Biology, researchers from Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden (XTBG) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences summarized recent findings on how compound leaves develop.Their work integrated decades of studies on model species such as tomato, Cardamine hirsuta, and key legumes including Medicago and pea, offering a clearer view of the genetic “toolkit” that shapes these elaborate leaves.

The development of a compound leaf begins with a simple peg-like primordium at the periphery of the shoot apical meristem (SAM). A key feature is the transient activity of the marginal blastozone, a lateral meristematic zone that allows leaflets to initiate.

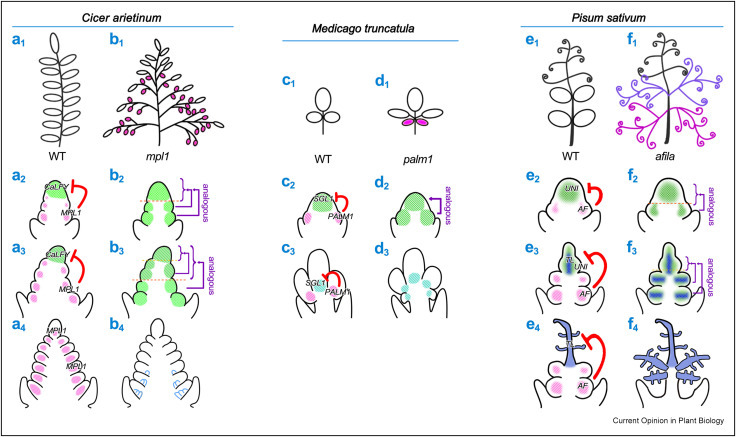

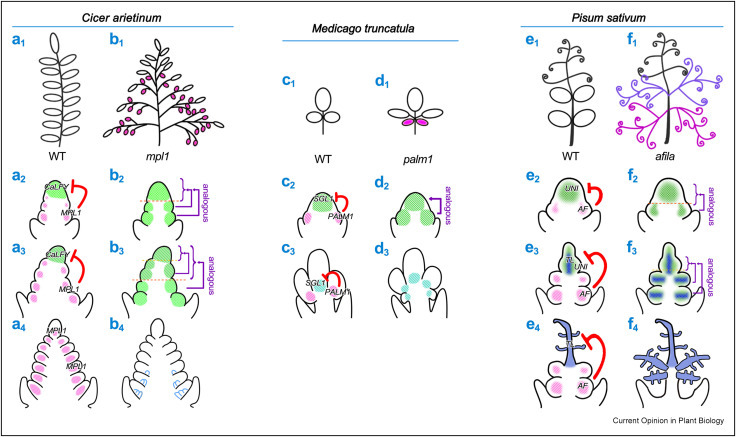

According to the review, a deeply conserved genetic toolkit guides a leaf bud to become a multi-leaflet structure. Central to this process are the KNOXI and LFY/FLO gene families.

"In most plants like tomato, KNOXI genes are reactivated to promote leaflet formation. But in many legumes, evolution has repurposed the floral gene LFY/FLO for this task, showing remarkable flexibility," said CHEN Jianghua of XTBG.

These core genes do not work alone. They interact with hormone signals (like auxin) that pinpoint where leaflets emerge, and with boundary genes like CUC/NAM transcription factors that demarcate regions between emerging leaflets, ensuring proper separation and individualization.separate the leaflets.

In the model legume Medicago truncatula, repressors including PALM1 finely modulate the activity of the LFY-type gene SGL1 to establish the correct three-leaflet pattern. Mutations in these repressors result in strikingly altered leaf morphology.

The regulation also involves adaxial-abaxial polarity genes, which interact with auxin to influence leaflet arrangement. Together, these genetic cues direct localized cell growth to form the mature leaf architecture.

Looking ahead, the researchers proposed that future research should leverage systems biology approaches, including single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, to map the complete regulatory network across species.

“Integrating phylogenetics with evolutionary developmental biology will clarify how genetic rewiring drives the stunning variety of leaf forms observed in nature,” said CHEN.

A conserved molecular module regulating compound leaf development in Cicer arietinum, Medicago truncatula and Pisum sativum. (Image by HE Liangliang)

Available online 31 December 2025