China-Lao PDR Transboundary Biodiversity Conservation Collaboration involves scientists from the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden (XTBG) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and the Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute (SEABRI) of CAS working jointly on scientific expeditions, of which three have been carried out so far. The scientists dive headfirst into the wealth of life hidden deep in mysterious Laos.

Tropical Diversity in Laos

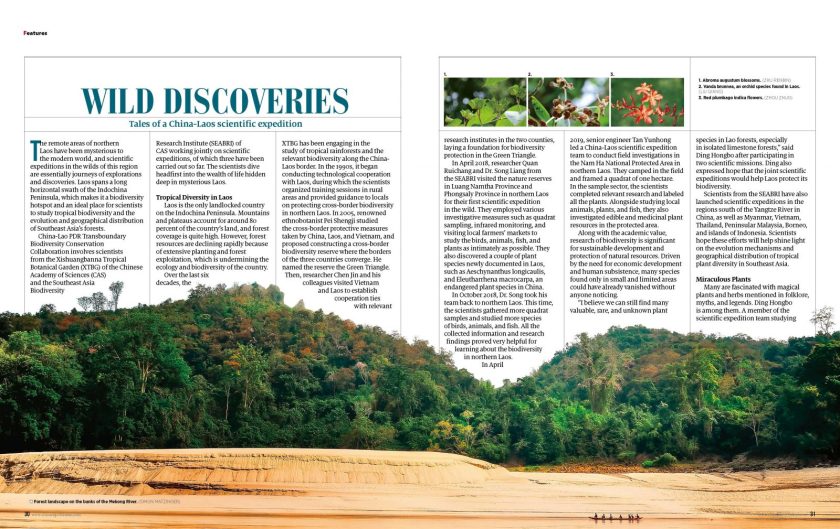

Laos is the only landlocked country on the Indochina Peninsula. Mountains and plateaus account for around 80 percent of the country’s land, and forest coverage is quite high. However, forest resources are declining rapidly because of extensive planting and forest exploitation, which is undermining the ecology and biodiversity of the country.

Over the last six decades, the XTBG has been engaging in the study of tropical rainforests and the relevant biodiversity along the China-Laos border. In the 1990s, it began conducting technological cooperation with Laos, during which the scientists organized training sessions in rural areas and provided guidance to locals on protecting cross-border biodiversity in northern Laos. In 2005, renowned ethnobotanist Pei Shengji studied the cross-border protective measures taken by China, Laos, and Vietnam, and proposed constructing a cross-border biodiversity reserve where the borders of the three countries converge. He named the reserve the Green Triangle. Then, researcher Chen Jin and his colleagues visited Vietnam and Laos to establish cooperation ties with relevant research institutes in the two counties, laying a foundation for biodiversity protection in the Green Triangle.

In April 2018, researcher Quan Ruichang and Dr. Song Liang from the SEABRI visited the nature reserves in Luang Namtha Province and Phongsaly Province in northern Laos for their first scientific expedition in the wild. They employed various investigative measures such as quadrat sampling, infrared monitoring, and visiting local farmers’ markets to study the birds, animals, fish, and plants as intimately as possible. They also discovered a couple of plant species newly documented in Laos, such as Aeschynanthus longicaulis, and Eleutharrhena macrocarpa, an endangered plant species in China.

In October 2018, Dr. Song took his team back to northern Laos. This time, the scientists gathered more quadrat samples and studied more species of birds, animals, and fish. All the collected information and research findings proved very helpful for learning about the biodiversity in northern Laos.

In April 2019, senior engineer Tan Yunhong led a China-Laos scientific expedition team to conduct field investigations in the Nam Ha National Protected Area in northern Laos. They camped in the field and framed a quadrat of one hectare. In the sample sector, the scientists completed relevant research and labeled all the plants. Alongside studying local animals, plants, and fish, they also investigated edible and medicinal plant resources in the protected area.

Along with the academic value, research of biodiversity is significant for sustainable development and protection of natural resources. Driven by the need for economic development and human subsistence, many species found only in small and limited areas could have already vanished without anyone noticing.

“I believe we can still find many valuable, rare, and unknown plant species in Lao forests, especially in isolated limestone forests,” said Ding Hongbo after participating in two scientific missions. Ding also expressed hope that the joint scientific expeditions would help Laos protect its biodiversity.

Scientists from the SEABRI have also launched scientific expeditions in the regions south of the Yangtze River in China, as well as Myanmar, Vietnam, Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, Borneo, and islands of Indonesia. Scientists hope these efforts will help shine light on the evolution mechanisms and geographical distribution of tropical plant diversity in Southeast Asia.

Miraculous Plants

Many are fascinated with magical plants and herbs mentioned in folklore, myths, and legends. Ding Hongbo is among them. A member of the scientific expedition team studying the botanical diversity in northern Laos, Ding was tasked with categorizing and taking pictures of plants growing in the quadrat. The expedition was fraught with difficulty and even danger, but curiosity for the unknown drove Ding and his fellows to venture deeper and deeper into the wilds. The chance to discover a new species is an attractive reward for their unremitting efforts.

“Research and study of Laos’ plants started as early as 140 years ago, but the country still does not have a national Flora for all the plants found in its territory,” commented Dr. Tan Yunhong. “To study the phytochorion in a floristic region, you have to know the composition of plant species and their respective distribution characteristics.” The flora of a specific area, according to species and distribution, can be categorized and documented in a publication known as “Flora,” usually capitalized to distinguish between the two meanings. “Flora” is the basic material for floristic study and an indicator of a region’s academic standards.

Expedition team member Liu Qiang has an acute fascination with orchids and years of experience studying the flower family in tropical areas. When researching an evergreen broad-leaved forest in Oudomxay Province, Liu was able to quickly and accurately recognize and record orchid species he saw. The Lao researchers accompanying him were quite amazed especially considering that some of the orchids he identified had not even bloomed. Liu explained that many orchid species in the forest were not new to him because he found similar specimens in Xishuangbanna, a Chinese prefecture near the forest. During nearly a month of field investigation, Liu researched 118 species of 48 genera of the Orchidaceae, of which six genera and over 30 species had never before been documented in Laos.

But like many other plants in Lao forests, the prospects for the orchid family are bleak because of the country’s deteriorating ecology and diminishing natural resources. Locals have been replacing many indigenous trees with rubber trees, teak, or other more profitable trees, which has undermined the local environmental balance and destroyed the habitats of many plants. Numerous indigenous plant species are getting decimated by massive exploitation.

To survive, reproduce, and adapt to their surroundings, plants generate various chemicals through secondary metabolism. All these naturally existing molecules are essentially molecular biodiversity, and often become gifts for mankind. For example, a willow bark extract opened the door to aspirin, a groundbreaking drug. Quinine, which was first isolated from the bark of a cinchona tree, and artemisinin, a lactone derived from Artemisia annua, are tremendously helpful in controlling malaria. Paclitaxel, a compound used for cancer treatment, was first found in Taxus bark.

Laos has many ethnic groups which have developed a long tradition and abundant knowledge on using herbal medicines for basic health care. Promoting the planting and collecting of specimens with edible and medicinal value can help poverty alleviation efforts. The Lao living in remote areas can collect the herbs that sell for decent money.

During the expedition, the team researched a total of six plant species of the garcinia genus, two of which lack any distribution records in China. One species that measured one to three meters in height seemed incredibly short compared to similar species of trees that normally grow quite tall. Its leaves were also comparatively small. The fruit of the species turns red as it matures and is quite delicious. The team is still studying the ingredient composition of the garcinia genus, and the results are expected to help facilitate sustainable development of Laos’ medicinal plants.

Aromatic plants are also abundant in Laos. In addition to flavoring food, such plants are also used in pharmacology, religious rituals, and cosmetics manufacturing. Ancient records show that aromatic plants traded along the ancient Silk Road were considered luxuries. Pepper, cinnamon, cloves, and ginger were once as precious as gold. Because aromatic herbs were one of the most profitable commodities to transport, the Maritime Silk Road was also known as the “Road of Condiments.”

Somsanith Bouamanivong, deputy director of the Biotechnology and Ecology Institute under the Ministry of Science and Technology of Laos, noted that many Lao foods use local ingredients which give them unique flavors. Aromatic plants remain an important facet of Lao food culture. Such distinct flavors stimulate the appetite, and aromatic plants are not only profitable—their cultivation often enhances protection of endangered plants.

Lost Species

“Dawn on the Lao countryside feels like a fantasyland,” said team member Zhang Mingxia. “I would imagine myself waking up in a village surrounded by fog, able only to see the top half of a temple hidden in the water vapor and hear gibbons roar from a distance as tigers and elephants wander through the forest. This is the most gentle side of nature in my mind.”

But Zhang’s dreamy trance was eventually shattered in a village 30 miles from Luang Namtha where she came upon the skull of a Malabar pied hornbill, a bird in the hornbill family. The village head showed her the skull and explained that he acquired it while hunting on a mountain 10 miles from the village. The village head told her to watch out for tigers deep in the forest.

While on another field research excursion, Zhang invited a local guide to help her look for the bird in the place the village head had mentioned. They walked more than 10 miles around the village and camped on a mountain ridge. Day and night, they could hear gunshots, and they knew local people were hunting. Hunters often cook on the roadside, so Zhang saw many feathers of various kinds lining the roads. After two days of sleeping on the mountain, she finally came to terms with the frustrating reality. The species she could identify from discarded feathers far outnumbered what she saw and heard. She had to accept that the Malabar pied hornbill might have already gone extinct in this area.

That village is not the only place undergoing such changes. Li Guogang and Sun Nan are researchers who specialize in monitoring and tracking mammals. During the mission, they discovered animal corpses frozen in refrigerators and antlers of sambar and other kinds of deer mounted on the rooftops of local households. The researchers did not expect to find specimens of such precious animals so easily after setting up numerous infrared monitors in the forest of Xishuangbanna. The animals they saw post-mortem might never be captured alive by a camera for a whole year. All they could witness were rigid dead bodies waiting to be boiled and eaten.

A 2019 article in Global Ecology and Conservation announced that the tigers in the Nam Et-Phou Louey National Protected Area in northern Laos had died out. The region was the only place in Laos confirmed to have tigers, so the article declared tigers extinct in the country. The author also suggested that leopards may face the same fate. Every time a species is wiped out on this planet, it becomes even more crucial to protect the surviving ones. The task becomes more pressing with each passing day.

Big birds and animals are the preferred targets of hunters. If local people inhabiting the areas around forests cannot escape poverty or benefit from protecting the environment, mapping out protected areas is useless. In the Shangyong Nature Reserve, a district adjacent to Laos’ Nam Ha Protected Area and a subsidiary of the Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve in China, an Indochinese tiger was photographed in 2007. It was the last time an image of the species was captured in China. Over the past three decades, species such as gibbons and large hornbills have disappeared alongside tigers.

(We thank the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden and the Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Sciences for their contribution to this article.)