Spinescence (a general term for the phenomena of spines, prickles, and thorns on plants) is an important functional trait shared by numerous plant families worldwide and mainly provides physical protection against vertebrate herbivores. Even though spiny plants are distributed worldwide, our understanding of their evolutionary history remains incomplete, largely due to a dearth of fossil records.

In a study published in Nature Communications, researchers from the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden (XTBG), the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), the University of Bristol, and the Open University of the United Kingdom report exceptionally rich assemblages of plant spine fossils collected from late Eocene (about 39 million years ago) sediments in central Tibet.

These fossils confirm an early diversification of spiny plants in the Tibetan region contemporaneous with the emergence of open, semi-wooded habitats by the late Eocene and early in the transition of central Tibet to full plateau formation.

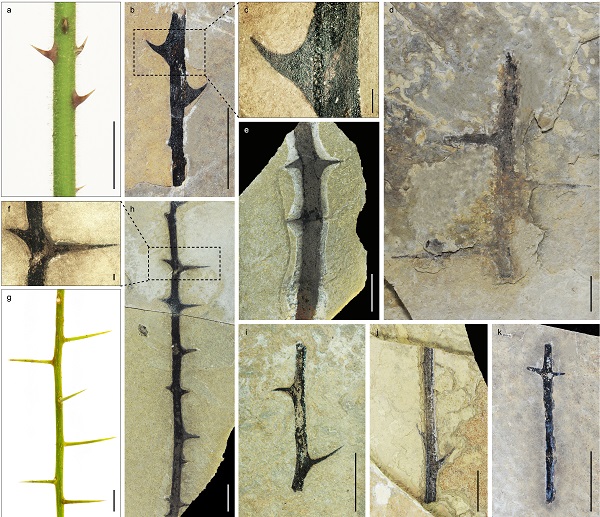

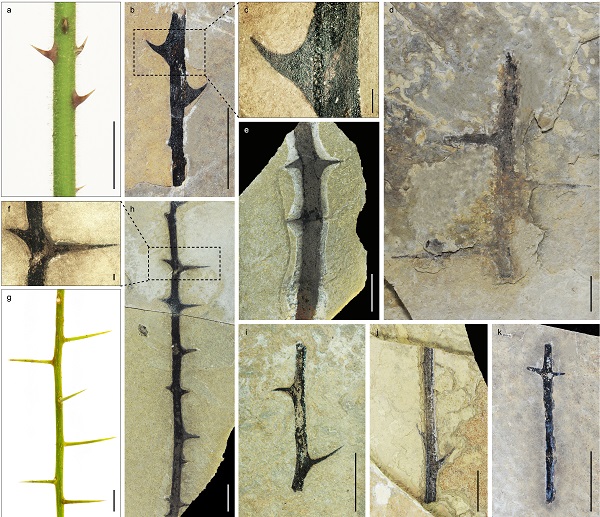

The researchers documented a total of 44 spine-bearing fossil specimens collected from two fossil localities within the central Tibetan Bangong-Nujiang Suture Zone: the Dayu (32° 20′ N, 89° 46′ E) and Xiede (31° 58′ N, 88° 25′ E) localities. They classified fossil spines into a total of seven morphotypes comprising prickles and thorns according to two criteria: Prickles originate from the epidermis of plant organs such as stems, leaves and petioles, whereas thorns are modified branches and contain internal vascular bundles.To investigate the emergence and early diversification of spiny plants, the researchers not only conducted molecular phylogenetic analyses, but also used proxy and modelling data to reconstruct the vegetation, climate, and herbivory that favored spiny plant evolution in central Tibet during the Eocene. In addition, they reconstructed the evolutionary history of spines across species of woody eudicots in Eurasia within the mega-phylogeny of plants.

According to ZHANG Xinwen of XTBG, the modelling and proxy data point to “a drying and cooling climate” in Tibet’s central valley by the mid-Eocene. This change was accompanied by an increase in elevation of about one kilometer about 47 million years ago.

Against this backdrop, the plant fossils record the beginnings of vegetation opening-up under a drying/cooling climate as the modern Tibetan Plateau grew from the late Eocene onwards. The observed spinescence marks the early development of physical defense mechanisms against large herbivore feeding pressure in the region.

“Our study shows that regional aridification and expansion of herbivorous mammals may have driven the diversification of functional spinescence in central Tibetan woodlands, about 24 million years earlier than similar transformations in Africa,” said SU Tao of XTBG.

Contact

SU Tao Ph.D Principal Investigator

Key Laboratory of Tropical Forest Ecology, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Mengla, Yunnan 666303, China

E-mail: sutao@xtbg.org.cn

Image of a typical spiny plant Gleditsia microphylla (Fabaceae) native in Asia. (Credit: ZHANG Xinwen)

Morphotypes of spiny fossils from the Eocene sediments of the central Tibetan Plateau. (Image by ZHANG Xinwen)

A spiny fossil from the Eocene sediments of the central Tibetan Plateau. (Image by ZHANG Xinwen)