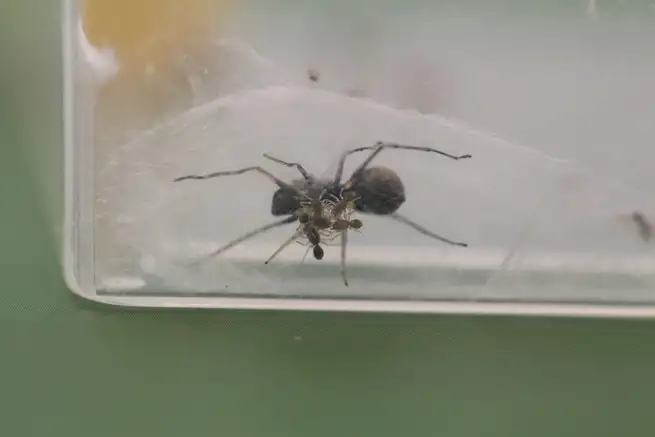

The jumping spider Toxeus magnus lives in China and Taiwan. Its appearance mimics that of an ant, but it’s parental behavior is surprisingly mammalian. The mother spider cares for the newborn spiderlings for up to 20 days—a long time for a critter whose entire lifespan is just six months to a year. During these first 20 days, she secretes a white fluid that’s rich in sugars and proteins, from its abdomen. The “milk” is crucial for the survival of the young spiders, and surprisingly, it contains four times as much protein as cow’s milk, , according to a new study published this week in Science.

“I thought it was remarkable, you don’t really expect spiders to be providing that type of maternal care,” says Jason Bond, an entomologist at University of California, Davis who was not involved in the study.

Researchers at Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Hubei University, and Kunmig Institute of Zoology noticed something strange about one particular group of spiders. While most mother spiders would leave the nest soon after birth, jumping spiderlings seemed to hang around the nest for far longer than most other jumping spider species. When the researchers brought the spiders back to the lab to get a closer look, they found that over a span of three weeks, the baby spiders grew consistently in size, even though the mother spider never bring food back for them to eat. Eventually, researcher Zhanqi Chen noticed something never seen before: The young spiderlings crowding around the mother’s abdomen, drinking a white fluid secreted from a reproductive organ used to lay eggs.

To test whether drinking this “milk” truly affected the survival of the little spiders, Chen and his collaborators ran a series of experiments. They painted white-out (yes, that’s correct) across the area of the mother spiders’ abdomens where the milk flowed from, blocking its secretion. All the baby spiders stopped developing and died days later, suggesting total dependence on the milk supply in their early days, the researchers write in the paper. In follow up studies, the scientists found that the milk was essential for the first 20 days of life only; afterwards the young spiders started to fend for themselves. But they still drank the milk every so often and the continued maternal care greatly boosted their ability to survive and thrive.

In the past, research on spider secretions has been limited to studying the critters’ precious silk, which is essential for creating necessary webs. As far as Bond is aware, this is the first time scientists have found spiders behaving this way.

“This is definitely a first,” says Peter Smithers, an arachnologist at Plymouth University in the United Kingdom who was not involved in the study, “but spiders are full of surprises.”

While definitely surprising, lactate-adjacent behaviors aren’t totally unheard of in other animals world, even cockroaches provide a crystallized milk for their embryos and pigeons produce a nice fluid in a body pouch for their young to nosh on. But it’s important to realize these creatures aren’t lactating in the same way as mammals, says Smithers. Mammals have special glands for milk production, which spiders (and roaches, for that matter) don’t have. So the “milk” could be the partially digested remnants of unfertilized eggs, Smithers suggests. That would be in keeping with other known spider behaviors, as some spiders will actually lay unfertilized eggs for their young to eat to give them plenty of sugars, fats, and proteins early on in life.

There are nearly 50,000 known species of spider in the world and we know a lot about a few and very little about the rest, says Bond. Uncovering a new behavior like this could tell us something about convergent evolution between distantly related species—mammals and arachnids—and inspire scientists to look more closely at our mysterious eight-legged friends.

And maybe in the far, distant future, we’ll all drink spider milk from giant dairy arachnids. Think of all the protein in just one, gloopy glass! What am I kidding, the giant spiders would definitely kill us all before it got to that point.